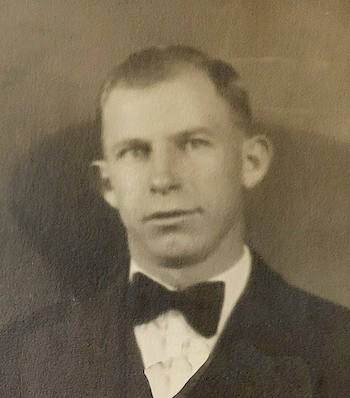

Carl Mishmash

History's Hidden Gems

More News Articles

by Holly Swigart

The Mishmash Strike - 1921 Pittsburg, Kansas

by Holly Swigart June 17, 2022

On August 31, 1898, Kate and Jacob Mishmash welcomed their first child, a baby boy they named Carl. They could not have known how important that date would become years later to thousands of coal miners in Southeast Kansas. Carl left school after 3rd grade and went to work in the coal mines with his father. When Jacob Mishmash died in 1914 from an illness brought on by years of breathing coal dust, young Carl became the family's primary breadwinner. This meant the family income was cut by more than half because like all the other children working in the mines, Carl was paid substantially less than an adult worker. His mother, Kate, struggled to make ends meet while stepping up to the challenge of raising five children alone. Carl was the only child old enough to work. The other children ranged in age from 2 to 9 years old, so Kate had her hands full. She worked as a dressmaker and took in laundry while Carl did what any teenage boy might do in this situation. He tried his best to fill his father's shoes and continued to go to work everyday at the coal mine. When Carl's 19th birthday rolled around, he was supposed to start receiving a grown man's pay of $5 per day. Unfortunately, he wasn't aware of the mine's policies and continued to work for 8 more months at the children's rate of only $3.65 per day. When Carl realized the mistake, he notified the coal company and they agreed to start paying him adult wages. However, they refused to give him the back pay he was due of nearly $200, a lot of money in 1918. Carl's mother came forward to verify his age, but she was reportedly accused of lying and the back pay continued to be denied. Several more years passed and still there was no payment. Kate had to give up their home and moved the family in with relatives. They had gone from being fairly comfortable, to being forced to live in a dirt floor basement.

When the local United Mine Workers District No.14 president, Alexander Howat, learned of Carl's story, he was determined to help young Mishmash get his back pay. After exchanging letters with the coal company representative for several months with no satisfaction, Howat ordered a workers' strike to bring attention to Carl's case. There was just one hitch. Striking, picketing and boycotting had recently been prohibited under a 1920 Kansas law. Any labor disputes were supposed to be settled using the newly formed Kansas Court of Industrial Relations. The creation of this new law was beginning to receive national attention. Could it be that Kansas had found a legal way to derail labor unions and render them powerless? Other states were considering following suit by passing their own laws designed to eliminate the workers' right to strike. Once again, the eyes of the nation were on Southeast Kansas.

Although Union leader, Alexander Howat, knew he could be arrested for calling a strike, he actually welcomed the publicity it would bring. Union leaders felt it was their duty to challenge this new law because it took away the only real power that workers had, the right to strike. All of the gains previously made by collective bargaining and organized labor might be undone if the Kansas Industrial Relations Act was allowed to stand. The case of Carl Mishmash was a perfect example. Carl had tried for years to get the money owed to him, but it took an organized work stoppage to force action on his case.

When the Industrial Court convened in an effort to determine whether or not Carl Mishmash was due the 8 months of back wages, they had to first establish his birth date. The Mishmash family bible had a record of births listed inside the front cover. However, it was not accepted as evidence. The midwife who had delivered Carl testified that she remembered being there, but since it was more than 20 years ago, she could not say with confidence the exact year. A number of other witnesses were called, but none of them could satisfy the court with real proof. Finally, a coal miner from Weir City named Michael Spahn came forward with some important information. Mr. Spahn had attended the christening which took place soon after Carl was born. He remembered that some of the guests were terribly upset by news they had just received from their native Austria. The Empress Elisabeth had been assassinated! The shocking story was told and retold during the christening, punctuated with cries of anguish as it spread through the crowd. The Empress Elisabeth and her lady in waiting had been about to board a ship in Geneva, when an Italian anarchist approached them. He appeared to stumble and lose his footing, bumping into the Empress. At first nobody, not even Elisabeth herself, realized that she had been mortally wounded. Her tight corset kept the stab wound from being immediately visible. She continued to walk some 100 yards and boarded the ship before collapsing. Moments later she died.

Although Mr. Spahn could not say for sure what year Carl Mishmash had been born, he knew for a fact that the christening took place right after the murder of the Empress of Austria. The judge quickly turned to the court clerk and ordered, "Get to the library and find the date of that assassination!" A packed courtroom anxiously awaited the clerk's return. When Mr. R.C. Dellinger, assistant clerk of the court, walked into the courtroom carrying an encyclopedia, a hush fell over the crowd. He read aloud to the court. "Empress Elisabeth of Austria was killed on September 10, 1898." At last, the proof they needed was established. Cheers rose up in the courtroom, which was filled to capacity. The coal company was ordered to pay Carl $187.64 in back wages, plus interest. But Carl refused to accept the interest. He insisted that the mine should pay exactly what he had been asking for all along, the wages he had rightfully earned. Carl, along with the union leaders, maintained that the Industrial Court was unconstitutional and therefore had no authority to award him anything more. Eventually the Supreme Court would agree and the Industrial Court was disbanded.

Carl and his wife, Mabel, spent the rest of their lives in Pittsburg. They enjoyed a happy marriage of more than 50 years, and celebrated birthdays into their 90s. Carl's mother, Kate, lived to be 100! Their story, like many of the immigrants who settled here in the Little Balkans area of Southeast Kansas, is a story of hard work and dedication to family. Carl Mishmash embodied both.

The account of Carl Mishmash, and his David & Goliath battle with the coal operators of Southeast Kansas, was told in union halls across the country. Although it was an important victory, the Mishmash case was just the beginning of a long, hard fight to eliminate the Kansas Industrial Court. And to be sure, the coal miners of Cherokee and Crawford Counties were going to be on the front lines for many more months to come. Union leaders: Howat, Dorchy, Maxwell, Fleming, Titus and McIlwrath were all arrested and charged with contempt for ordering the Mishmash strike. Alexander Howat stood up in court and addressed the issue of the right to strike with his usual fiery enthusiasm, "I could hardly believe that in free America, this great democracy, they would arrest us for trying to prevent the greedy operators from robbing a widow!" The courtroom erupted with wild applause and boot stomping. Judge Curran threatened to clear the courtroom. Howat and the others were convicted and sentenced to one year in jail. Thousands of coal miners responded by vowing to stay out on strike until the union leaders were released. They filled the streets outside the courthouse chanting, "One year jail, one year no work!" And so began the long and difficult strike of 1921.

Photo courtesy of the Mishmash family.